Eye Books is a small, independent publisher championing extraordinary stories and overlooked voices since 1996. We publish bold fiction and non-fiction, work closely with our authors, and take pride in bringing unique books to adventurous readers.

‘A chilling and politically astute dystopia ’ Jane Rogers

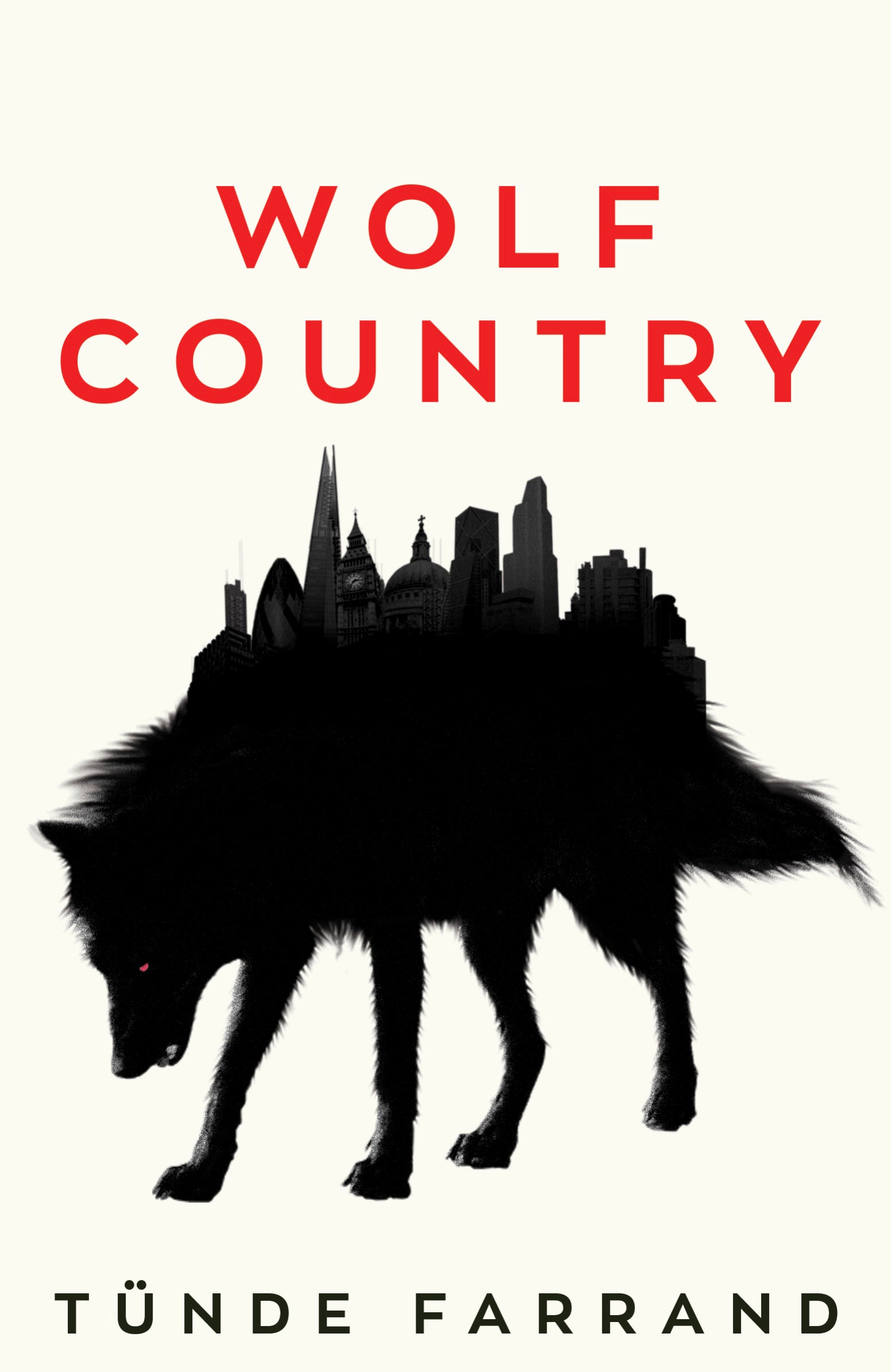

London, 2050. The socio-economic crisis of recent decades is over and consumerism is thriving.

Ownership of land outside the city is the preserve of a tiny elite, and the rest of the population must spend to earn a Right to Reside. Ageing has been abolished thanks to a radical new approach, replacing retirement with blissful euthanasia at a Dignitorium.

When architect Philip goes missing, his wife Alice risks losing her home and her status, and begins to question the society in which she was raised. Her search for him uncovers some horrifying truths about the fate of her own family and the reality behind the new social order.

Wolf Country is a powerful dystopian vision in the spirit of Black Mirror and Never Let Me Go.

‘Gripping’ The i Paper – top debut novels of 2019

‘Wolf Country will chill your heart and make you sick at the possibility of such a cruel and politically unsound world. Tünde Farrand absolutely nails dystopia and its unsettling predictions, with incredible writing’ Buzz Magazine

‘A chilling and politically astute dystopia which grips the reader from start to finish. Sci-fi in the tradition of Wyndham, with characters I really cared about, in a terrifyingly altered world’ Jane Rogers, winner of the Arthur C Clarke Award

‘I love Tünde Farrand’s dystopian novel, more pertinent than ever following recent events. Rarely do I pick up a book and not be able to put it down. Her storytelling and descriptions are exquisite’ Ruth Millington

‘Farrand’s stunning debut novel...is an excellent example of taking existing social phenomena and divisions and formalising them into a dystopian setting—in this case, class and inequality... [Her] real skill here is in drip-feeding the reader with details until the true horror of the book’s setting is revealed’ Electric Literature

UK postage is free if you spend £20 or more