Eye Books is a small, independent publisher championing extraordinary stories and overlooked voices since 1996. We publish bold fiction and non-fiction, work closely with our authors, and take pride in bringing unique books to adventurous readers.

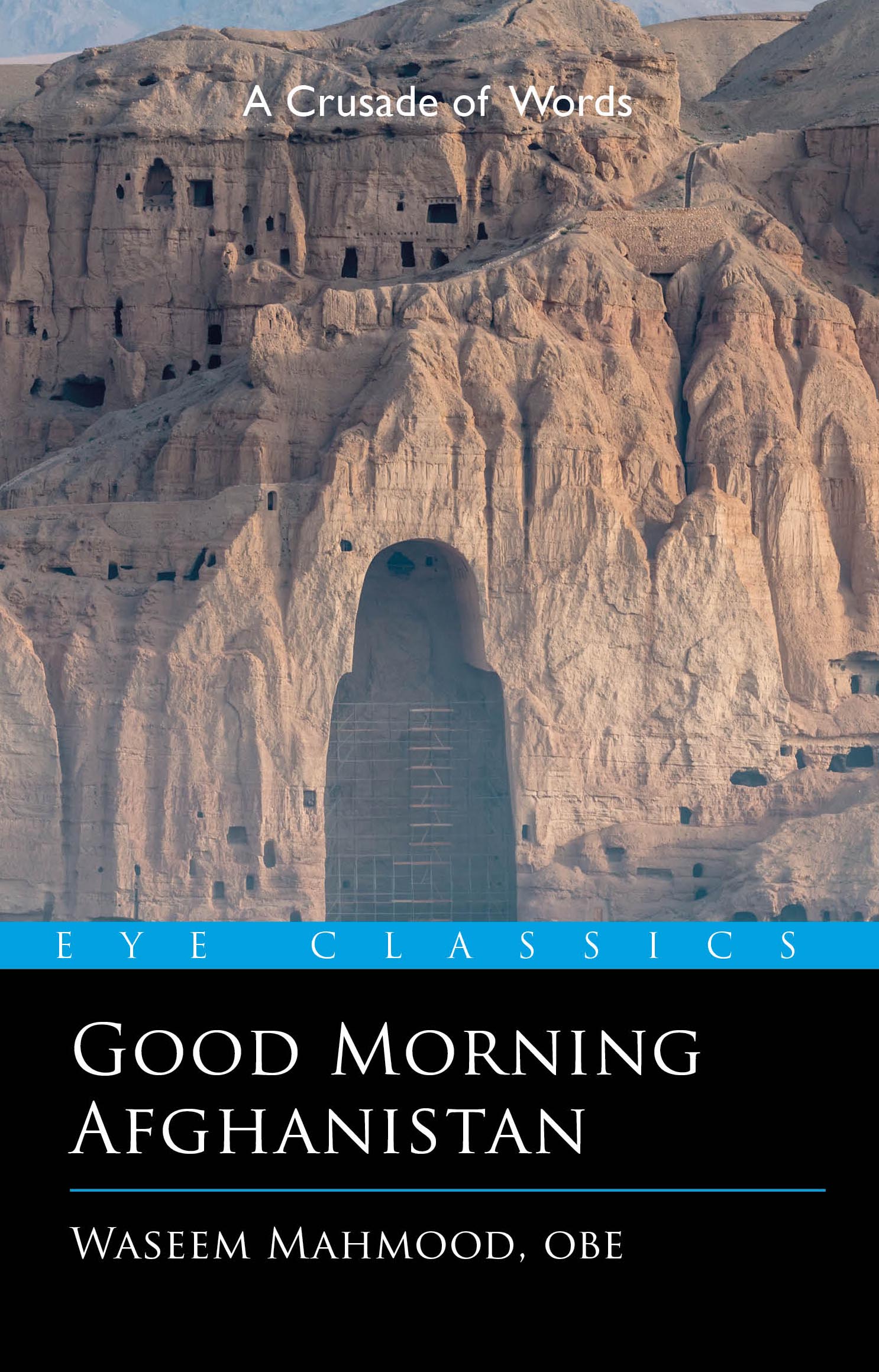

After the fall of the Taliban came a radio station with a mission

It is a time of chaos. Afghanistan has just witnessed the fall of the oppressive Taliban. Warlords battle each other for supremacy, while the powerless, the dispossessed, the hungry and the desperate struggle to survive.

In these days and months of bleakness, suffering and want, a glimmer of hope emerges – in the form of a spirited little breakfast-time radio programme, Good Morning Afghanistan.

This book is a true account of how an intrepid band of media warriors help a broken nation find a voice through the radio. Over the airwaves a land ravaged by decades of war starts to fight with words instead of weapons.

‘Vividly describes how it feels to be thrown in at the deep end’ The Economist

‘This is a story of the struggle and cruelty that afflicts the ordinary people of this land, but the ideals of hope and humankind’s ceaseless quest for freedom shine through in this brilliant work’ San Francisco Book Review

‘A magnificent book. Freedom comes in many forms – the most powerful is self-expression and by means of Good Morning Afghanistan, countless Afghan women and children teach one another how to be free’ Sacramento Book Review

UK postage is free if you spend £20 or more