Products

-

A Circle Outside -

A Long Shadow -

A Raindrop in the Ocean -

A Right Royal Face-Off -

A Summerstoke Affair -

A Tangled Summer -

Above the Law -

Aftershock -

All God’s Creatures -

All the Beautiful Liars -

All Will be Well -

An English Library Journey -

An Isolated Incident -

Anyone for Edmund? -

Appius and Virginia -

Arctic Insanity -

Ask an Adventurer -

At the Deep End -

Baghdad Business School -

Banana Devil Cake -

Beneath the Streets -

Bodily Fluids -

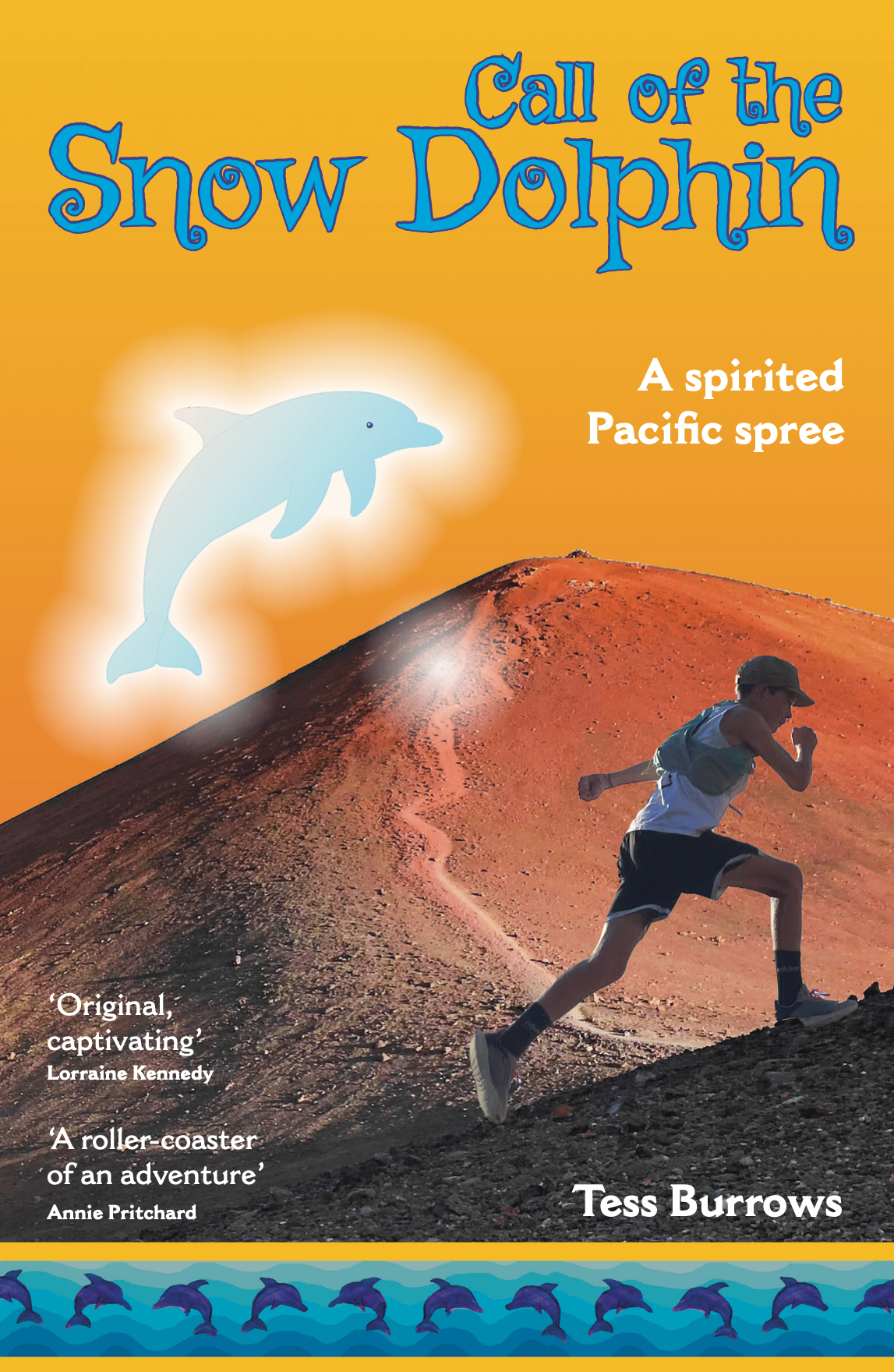

Call of the Snow Dolphin -

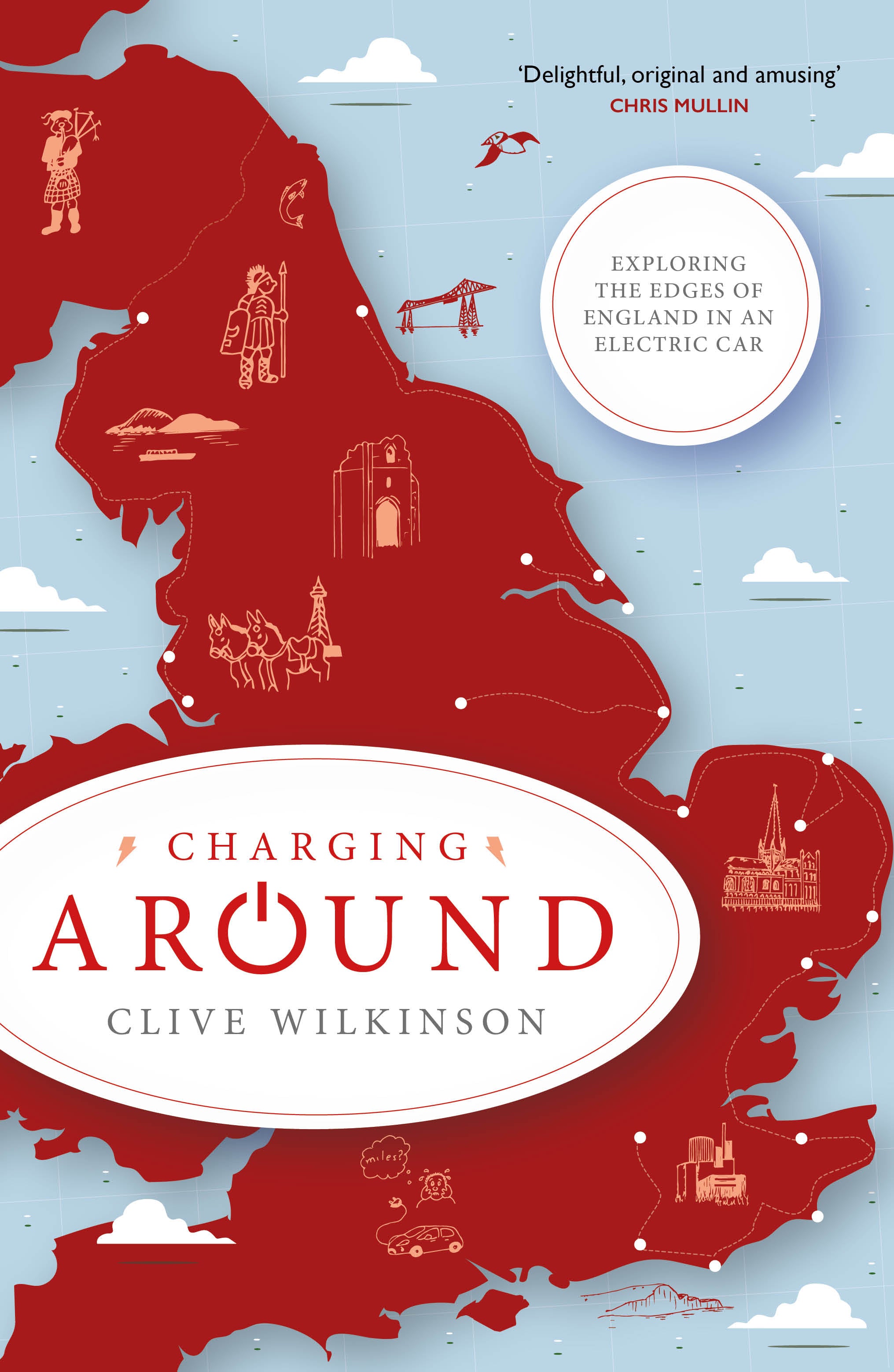

Charging Around